Hormones, Homeostasis, and Why You (Probably) Need Carbs

SummaryIn this article, I explore:

|

It starts so innocently…

If you have any interest in health, fitness, and nutrition, you probably have at least some awareness of how sugary, crappy food contributes to poor health, inflammation, obesity, and insulin resistance.

Naturally, you as a conscious eater want to do The Right Thing. So you start reading labels and eating whole foods. You get rid of sugar, or at least cut your intake way down.

Pretty awesome start. You could probably stop right there and still be better off than most of the Western population.

But of course, every little positive, health-affirming step inspires you to take another.

You move towards higher-fibre, less-processed versions of traditional grains. Or you cut grains out completely. You probably end up with a more or less ancestral/Primal-style way of eating.

Again, you could quit right here. In fact, you probably should. Now you’re at 99th percentile of food and lifestyle quality. And with some practice, you could live that way pretty easily and sanely.

…and then…

You keep reading. You swirl down into the blogosphere of half-baked opinions, speculation, anecdotal evidence, pseudoscience, and what my colleague Dr. John Berardi so aptly terms “hysterical negativity”.

This is where the rabbit hole of madness begins.

Because you start to think: What else could I do to be better? How could I nudge this generally pretty decent situation into awesome? Into perfect?

And naturally, you work harder. You train harder. You Paleo harder. You cut harder. You pound that shit in. To. The. Ground.

You’ve heard that cutting carbs is primal. So you go for rock bottom.

You’ve heard that cave people never ate Food XYZ so you’re restricting everything that isn’t a dead animal or something green.

You’ve heard that wasting an hour on a “workout” is bullshit. Cave people got ‘er done hard and fast. Ready for anything. So you trash yourself with 100 rapid-fire power cleans or 2 miles of sprinting sled drags or box jumps until you can literally hear your Achilles tendons sobbing. You do it again the next day. And the next. And the day after that.

You throw in some fasting just for good measure. Cave people didn’t have 24 hour buffets, after all.

For a while, this feels great. Heroic.

You often have lots of energy because you’re running on the fumes of your body’s stress response — natural painkillers and adrenaline. Your skin glows and your joints feel fantastic because you’re not eating processed junk that inflames them. You’ve shed some pounds and are sliding effortlessly into your skinny jeans.

Plus let’s be honest. You’re also feeling the high of being smug as shit now.

You’re a zealot. A recent convert. Fuck the hatas and deluded drones of Big Food. You have your Cavepeople Club and it feels stupendous — or is that the endogenous opioids your body is pumping out to kill the pain of another vomitworthy workout?

This is how hardcore you are. |

Yeah, this feels great. Until it doesn’t feel so great.

6 months, maybe 12 months, maybe a couple years along, the cracks start to appear.

First, it’s nothing special. Maybe a funny period or two. It’s hard to sleep lately too. But whatever, last month was kinda stressy with work and whatnot. No biggie.

You start to put on weight. Your belly’s looking a little bloated. Or you retain water. You can see it when you take your socks off, like a railroad of little dents in your ankles.

Well that’s a little odd but hey, maybe you just need to clean up that diet again. After all you’ve been having some food cravings, maybe indulging a little too much in “forbidden” foods. Back to Paleo-ing harder and slicing those carbs down.

That doesn’t work. Now your eyebrows are looking weird — sorta thin on the ends — and is that hair in the drain? Or worse, on your upper lip? Your skin, once incandescent, is starting to look sallow. A few zits are popping up too. Damn it, you thought you left adolescence behind!

You’re cold. Constipated. Starting to lose your mojo. Small indignities are starting to pile up — little naggity injuries, a snuffle or cough that won’t go away, waking up feeling crusty and creaky.

Then — oh jesus fuck — the weight really starts to pile on. And you can’t seem to do anything to stop it. That shit is a fast-moving freight train and you’re tied to the tracks. You panic. Train harder. Paleo harder. Harder.

All hell breaks loose.

Your mood swings into anxiety, sadness, and screaming, random rage are turning you psychotic. Your partner, children, and/or friends dive for cover behind the furniture when you walk into a room. You feel like you’re going nuts. You imagine you can hear the scale laughing at you as it conspires with the waistband of your pants.

Your food cravings are making you mental. You’d consider having sex with a delectable, forbidden loaf of bread, if you had a sex drive any more. But your libido’s gone, along with your period. (Or conversely, your periods are crushing you with cramping waves of pain and uterine tsunamis.)

What the hell just happened?

Hopefully, you haven’t gotten this far. Hopefully, you’re just reading this for interest because you’re simply considering cutting down your Pepsi intake. Great.

Stay at those early stages of nutritional and hormonal sanity. Make a few key improvements (such as eating more vegetables and getting rid of garbage non-food) and then get on with the rest of your life.

For the rest of you… if you recognize yourself… you might want to keep reading.

In this article, I’ll explore:

- the general concept of homeostasis;

- some hormonal effects of disrupted homeostasis and the stress-survival response;

- why — given these hormonal effects — you should consider your total stress load, including nutritional stress;

- why — again, given these hormonal effects — you might also consider keeping your (healthy) carb intake relatively higher than is conventionally recommended in lower-carb circles; and

- what to actually do to put this into practice.

Disclaimer

Now remember, we still don’t know everything there is to know about hormones and homeostasis. And the phenomenon of humans intentionally restricting nutrients while training hard under the environmentally and psychologically stressful conditions of 21st century society is still relatively new.

Some of this is speculative or informed guessing; extrapolation based on experiential and clinical data that is still incomplete.

I’ve personally coached hundreds of women and overseen the coaching of hundreds more in our Lean Eating coaching program at PN (which originally lasted 6 months and now goes for 12, giving us some pretty awesome longitudinal information). To date, about 10,000 people — probably about 2/3 of them female — have done the program.

So I’ve gathered some pretty good real-life applied data on women specifically. (Unlike many internet warriors who have never trained a single — never mind a female — client. Just sayin’.)

Nevertheless, I’m simply thinking through some observations and connecting some dots.

This isn’t gospel, nor is it the full answer. Biology is complicated shit.

It’s important for you to recognize this. Many “experts” won’t acknowledge that limitation.

YOUR body is YOUR best data point.

I’ll give some concrete suggestions about how to be your own science experiment, and how to know stuff is working (or not) at the end of the article. (If you want to skip the boring and possibly wildly speculative explanation, skip to the end.)

Go grab yourself a sweet potato to gnaw on, and keep reading.

Homeostasis

Some people assume that homeostasis is a kind of rigid “everything stays the same” situation, like a weird cloned universe of Stepford wives where deviation is punished.

I like to think of homeostasis as more of a dynamic balance, like standing on a moving train. To me, homeostasis is a kind of physiological aikido, always shifting and moving and coming back to centre after being disrupted.

There’s a flow to homeostasis. Nothing is stagnant or stuck. Homeostatic mechanisms are always like, “Hey y’all! What’s goin’ on now? What about now?” and then excitedly coming up with shit to do, kind of like toddlers who ask three billion questions in the space of a five-minute conversation and want to go on a roller coaster ten seconds after getting off a merry-go-round.

Homeostasis is a holistic phenomenon. Homeostasis is about the system. The big picture. The whole enchilada.

So homeostasis will throw some lesser shit under the bus in the service of the greater good, if needed.

Here’s a very scientific ranking list:

Most important shit

Avoiding death / staying alive

Breathing

Using (and if necessary, conserving) whatever fuel is lying around

Kinda important shit

Fighting off pathogens

Getting and storing additional nutrients

Regulating fluid and electrolytes

Meh, will get around to it

Reproducing

Repairing & growing

Recovering & regenerating

The hormone hierarchy

Hormones are often organized hierarchically.

Hormone A (say, in the hypothalamus) will tell Hormone B (say, in the pituitary) to tell Hormone C (say, in the gonads) to do something (or not). There’s often a clear chain of command: Hormone A is the boss. Hormone B is the middle manager. Hormone C is the worker bee.

Central vs peripheral hormones

Hormones secreted in the brain are typically centralized controllers or regulators. They’re like Mission Control, scanning the whole situation and getting a global sense of what to do next in order to maintain homeostasis.

Hormones secreted elsewhere — say, in the digestive system, adipose (fat) tissue, or gonads — can have both local and systemic effects. These peripheral hormones often have a relationship with what’s next door to them. For instance, hormones in the gut can respond to particular nutrients, such as cholecystokinin (CCK), which responds to the presence of fat in the small intestine.

Peripheral hormones can also act as sensors. They’re like worker bees out in the field, letting the boss know what’s happening on the front lines.

Most peripheral hormones have some systemic effect on brain function. So, CCK senses fat and protein in the gut, but it may also regulate satiety, sleep and wakefulness, and stress and pain sensation in the brain.

Mission Control is always gathering information about the state of the organism. That information can come from all kinds of sources, e.g.

- fuel (such as glucose) circulating in the blood

- adipose (fat) tissue

- environmental cues — light/dark cycles, temperature

- pain, pressure, movement, and other sensations

- what’s in the digestive tract

- our psychological-emotional state (including our thoughts and self-talk)

- mechanical loading or work (e.g. getting your sweat on)

- etc.

Hormonal interactions

Hormones interact with one another. We don’t know all the interactions yet. Nor do we know all the things a given hormone may do. We are learning all the time.

We can guess at some of the interactions based on things like:

Hormone receptors — If a given tissue has receptors for Hormone X, it’s a good bet that Hormone X does something with that tissue.

Hormone deficiencies — If a person or animal has a known hormone deficiency (whether genetic or as a result of some other factor such as removal of the gonads), we can look at what happens to them.

Hormonal excess — We can also guess at interactions by looking at the effects of hormone excess. This could be endogenous — or self-produced — secretion, or exogenous — i.e. from outside, perhaps something like an injection directly into a given site of action, such as the brain or the GI tract.

Molecular structure & synthesis — Nature is thrifty and biochemistry is sorta lazy. So many hormones are closely related in their makeup. Similar pathways govern hormonal synthesis, rather like intersections in busy city streets controlled by traffic lights and detour signals.

Sometimes you get a stoplight. Sometimes you can drive right on through. Sometimes you have to take a detour because something’s under construction. Sometimes you choose a different path because you’re cycling or walking instead of driving. Or whatever. You get the idea.

Even though the roads are the same, you don’t always take the same route. With hormones, things like genes or environmental cues or other hormones can be the traffic lines, stop signs, randomly placed pylons, or other switching mechanisms.

Symptomatology — The best way to know for sure what a given chemical is doing in our body is to measure it (or its metabolites) directly. But we can also look at symptoms.

This is often useful in cases where someone doesn’t show low or high hormones by a clinically defined range, but all their other symptoms say that those hormones are low or high for that individual. After all, reference ranges are statistical norms based on particular types of measurement methods, and biological organisms have a way of screwing up the tidiness of sorts of things.

For example, if you started out with 550 units of Hormone X, and you suddenly drop to 150, that’s a problem for you even if the clinically accepted “normal” reference range might be 100 to 600. And even if everyone else in the known universe swears that you shouldn’t have an issue if your Hormone X is over 100. Well, you fucking do have an issue because your body is used to being at 550 and now it ain’t, so that’s that.

We can also make working hypotheses based on physiological features like age, sex, ethnic background, bone density, and the way that body fat is being deposited.

So, key points here:

- There are central and peripheral hormones.

- These hormones interact with each other.

- Central hormones tend to be “master controllers” or regulators of whole-body functions.

- Peripheral hormones tend to act locally (i.e. wherever they are secreted) but also feed information back to the central controllers, and often have centralized actions too.

- Hormones are complex. We don’t know all the roles nor interactions yet, but we can guess.

- Optimal hormone levels can be quite individual.

Surviving vs. thriving

Recall the very scientific list of key body functions. Notice how “don’t die” is right up near the top and “reproduce” is near the bottom. Also notice how recovery, growth, and repair are luxuries while “get away from danger” and “use/store nutrients” are more like necessities.

As a shorthand, you can think of this prioritization as the difference between surviving and thriving.

People may say “Oh, you only need __ to survive.”

Well, you only need a little water and perhaps the occasional electrolytes every day to survive quite a long time in an underground hole while your body feasts on its stored fat and muscle. People have survived in the wreckage of collapsed buildings for several days.

But nobody would really recommend lying under a slab of concrete while contemplating your imminent demise and trying not to use up all the oxygen as a path to optimum wellbeing.

Nutrients & survival

Thus, surviving, for our bodies, means using only the nutrients we need to not immediately die.

In an acute-survival situation (the proverbial running-away-from-the-tiger scenario everyone loves to imagine as part of the daily routine of Paleolithic life), your body frees up glucose and free fatty acids. Fast fuel. Go! Run like a mofo! If those nutrients aren’t used right away, they go back into storage.

In a chronic-survival situation (such as starvation), the body starts to slow the engine and ration the nutrients, like WWII where everyone was hoarding cigarettes, butter, and stockings.

In neither case do you digest well and adequately. Your digestive system largely shuts down when stressed.

Motility is affected (so you get either plugged up or it’s “clear the decks!”). Your sense of taste is affected. You might feel nauseated or dyspeptic. You may lose your appetite or want to roll up the world in a burrito and eat it slathered in chocolate sauce.

Nor do you partition nutrients in a way that supports a lean, healthy, muscular body. It’s hormonal slash and burn. Fight, flee, or freeze. Dump the ballast. Survival by any means necessary.

Finally, the “nice to haves” — reproduction, rejuvenation, growth, and long-term regeneration — are not on the radar at all. No resources are allocated to these things beyond what’s needed to keep you from bleeding out.

You might get “stuck” in a rut of chronic inflammation as your body musters the defenses and blasts the system with trained killer cells (but forgets to tell the immunological SWAT team to calm down and stop shooting everything). Or, eventually, your immune system might just give up and go on vacation. Then you’re a sitting duck for every Tom, Dick, and Helicobacter pylori lying around.

Here’s a really important point, so pay attention:

Our bodies treat chronic nutrient restriction as a stress-survival situation.

That can be:

1. Overall energy restriction — consistently consuming significantly less energy (in the form of calories) than you expend (through activity and in basic metabolic functions).

2. Significant restriction of particular macronutrients — consistently consuming little to no fat, and/or protein, and/or carbohydrates.

3. Mild to moderate restriction in a context of other stressors — like doing #1 or #2 in the middle of an also stressful life, disrupted sleep, heavy training load, etc.

The big picture: cumulative load

Dig it? Are you putting the pieces together yet?

It’s holistic, baby. Homeostasis. The whole system. Your big fat life.

Everything from your environment, to your sleep, to circulating pathogens, to how much sleep you get, to your mindset and attitude, to your relationships, to the frequency and intensity of your daily movement, to your age, to your “stress blueprint” and natural resilience, etc. etc. plays a role.

If we took your eating habits out of the equation for just a moment… think about all the other factors in your life, right now, that could potentially be stressors. Just think. Really roll that around in the ol’ noodle.

Now, on top of that stress pile, add nutrient restriction. Add one more straw to the camel’s back.

See the problem?

At this point, you might be saying Oh great, does that mean I am doomed to never lose weight? That I have to quit anything strenuous? Are you saying if I don’t eat Twinkies with every meal I am going to die?

Of course not. I am saying three things:

Thing 1. Consider your whole life in totality. The whole system from macro to micro. What stressors are currently operating for you — system-wide — right now?

Thing 2. If you want to restrict energy or particular nutrients, you must balance the seesaw in other ways. If you add one stressor you must take at least one other stressor away, and/or chase recovery and restoration actively. If you are eating less you must also calm the fuck down, get some sunshine and vitamin D, and sleep. Don’t keep jacking yourself up with more control, more restriction, more heavy training, more life stress, more Type-A bullshit.*

Thing 3. Past a certain point, that seesaw is going to flip you off anyway. Laws of physiological homeostasis, I don’t make ’em up.

*I’m a recovering Type A perfectionist nutcase myself, so I smell your kind a mile away.

Regulation of “need to have” and “nice to have”

Which brings us to one major way that priorities are regulated in the body: hormones and cell signaling molecules. A small number — say, a zillion or so — of these molecules are involved in maintaining homeostasis and an organism’s health.

We’re only going to look at one for the most part: growth hormone.

(Don’t get too caught up in fetishizing a single hormone or substance, as many people do. Indeed, focusing too much on a single substance — such as insulin or fructose — without considering the bigger picture and physiological individuality has arguably gotten us here in the first place. Just get the general idea that this is one possible pathway through which a homeostatic and stress-survival response might operate, in concert with many other things.)

Growth hormone

Growth hormone (GH) is secreted in the brain — in the pituitary gland, to be exact. Again, any hormone secreted in the brain probably has a good reason to be there; and GH is indeed a very useful and important hormone.

In the right doses, GH is good stuff.

GH is involved in growth and repair, as its name implies. One of the biggest pulses of GH occurs during puberty. In adults, GH gradually declines (which means that eventually, broken parts don’t get fixed so well).

GH increases lean body mass (including bone density) and helps keep the thyroid humming.

GH increases resting energy expenditure (REE) — which, interestingly, appears to go up independently of LBM or thyroid hormone conversion. In other words, GH also increases REE by other mechanisms than simply the larger demand of all that extra bone, muscle, and tissue, or the work of the thyroid.

GH is pulsatile — secreted in little zips and zops, blips and blops. One major blip happens once we drop into deep sleep; other smaller blips happen a few hours after eating.

GH is also generally higher during periods of physical stress. Keep that in mind.

GH, women, and exercise

GH is secreted more often in female than male bodies.

In fact, many folks feel that given women’s relatively lower levels of testosterone, GH may be one of the major hormones involved in building strength and muscle in women.

This is especially true when doing heavy weight training and/or intense, metabolic-conditioning-type workouts that suck oxygen and feel horrible while you’re doing them (but awesome when you’re done, once you stop making whoopie with the floor). Want a quick trip to GHville? Knock out a set of 20-rep squats the old fashioned way.

Remember, physical stress → MOAR GH.

|

GH activates lipolysis, or the use of stored body fat (particularly visceral fat) for energy. It also helps skeletal muscles use triglycerides (a form of lipid, or fat) for energy.

There is some evidence, however, that GH does not stimulate lipolysis as effectively in women, older folks, nor obese people, which may explain why younger, often relatively leaner men seem to do better with intermittent fasting.

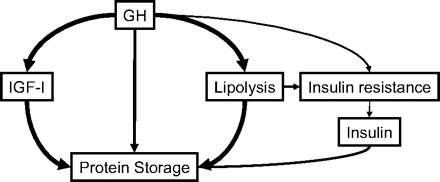

GH, insulin and IGF-1

GH interacts closely with the same pathways as chemical signals that respond to blood glucose levels — namely, insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1). There is “crosstalk” between the pathways stimulated by GH, insulin and IGF-1.

Some folks speculate that this is because GH and insulin-like peptides such as IGF are evolutionarily very old, pre-dating structures such as the pancreas, which secretes insulin.

GH has a complex relationship with these other peptides and hormones. Frinstance:

- GH stimulates β-cell proliferation, insulin gene expression, and insulin biosynthesis and secretion

- GH may inhibit the action of insulin, which is to drive glucose into cells.

GH and protein synthesis

Probably mediated by IGF-1, GH stimulates anabolic protein metabolism while inhibiting protein breakdown, which basically means getting swole. Under stress and/or fasting conditions this means that LBM is preserved as well as possible.

Cool… GH is good, right?

OK, higher GH sounds pretty nice so far.

Who wouldn’t want better growth and repair, higher protein synthesis, and better fat mobilization from visceral fat, maybe to be used as skeletal muscle fuel?

GH and triglycerides

Well, funny story, eheheh. GH may help release fat from visceral adipose tissue… but it also seems to dump triglycerides into the liver.

It’s not clear yet whether this is due to GH suppressing fat mobilization/oxidization or the creation of new fat storage (aka lipogenesis), but either way, you don’t want fat in there. Left unchecked, this fat deposition could lead to hepatic steatosis, or fatty liver, which is one of the leading causes of liver diseases in the 21st century industrialized world.

Oh, and by the way, high GH might also dump a little extra triglycerides into skeletal muscle too. Whoops!

Anorexics, in whom GH is often high, show a disrupted cholesterol profile relative to controls, although the exact nature of this depends on the type of restriction (e.g. restriction without binge-purge, restriction with binge-purge, etc.).

GH, insulin resistance, and stress

High GH can also induce insulin resistance, a situation in which cells stop “listening” to insulin’s signals. In insulin resistance, insulin has nowhere to drop its load of glucose, but of course more glucose keeps coming in, so both high insulin and high glucose end up roaming around the body causing all manner of nastiness.

Image from Møller & Jørgensen 2009. |

Frinstance:

In the late 1990s, a large multicenter study including more than 500 patients in the acute phase of severe critical illness reported that high-dose GH treatment doubled mortality from 20 to 40%. The detrimental outcome was associated with significant elevations in blood glucose levels despite more than a doubling of insulin administration in the GH-treated group. (Møller & Jørgensen 2009)

So even though doctors tried to fix the glucose issue with insulin administration, the problems remained. Of course, this is an extreme case involving supplemental GH in critically ill people, but still…

Two known mechanisms that stimulate insulin resistance: lack of sleep and stress. Frinstance:

- A recent study in mice showed that psychological stress could induce insulin resistance.

- High GH along with stress hormones (glucocorticoids) is a factor in insulin resistance and progression to type 2 diabetes and CVD.

Recall that in conditions of stress (e.g. starvation, physical or psychological stress), GH is the predominant anabolic hormone that helps conserve protein and oxidize fat.

As one review of GH actions explains:

When subjects are well nourished, the GH-induced stimulation of IGF-I and insulin is important for anabolic storage and growth of lean body mass (LBM), adipose tissue, and glycogen reserves.

During fasting and other catabolic states, GH predominantly stimulates the release and oxidation of FFA, which leads to decreased glucose and protein oxidation and preservation of LBM and glycogen stores.

OK, interesting. GH actions are context-dependent. Stress or no stress. Huh. Let’s think more about the evolutionary reason for that. Keep reading!

This ability of GH to induce insulin resistance is significant for the defense against hypoglycemia, for the development of “stress” diabetes during fasting and inflammatory illness, and perhaps for the “dawn” phenomenon (the increase in insulin requirements in the early morning hours).

Go back to survival. In stress-survival situations, the body could not give two shits about insulin resistance, any more than it cares that you might break a toenail running away. Insulin resistance is chronic. Rampaging tiger about to nom your face is right now.

GH and leptin

High circulating GH may also lower leptin.

Leptin, secreted by our adipose (fat) tissue, is one of those peripheral hormones that is also a sensor. It’s like our “fuel-o-stat” — the sensor and signal that tells our bodies that we have enough nutrients and stored body fat for a rainy (or hungry) day.

Typically, fatter/well-fed people have more leptin, while leaner or chronically hungrier people have less.

This means that for most folks, there’s probably an approximate leptin set-point.

Drop too low (by restricting intake too harshly or getting too lean for your unique metabolic blueprint, particularly under stressful conditions) and your fuel-o-stat will fire up. You’ll start getting hungry. Real hungry.

Conversely, put on a lot of body fat and at some point (if the machinery is working properly, which it often isn’t), your fuel-o-stat will say “Thanks, that’s cool, I’ve had enough” and kick in the satiety mechanisms.

Thus: As far as our fuel-o-stat is concerned:

- Leptin low → potential starvation → more hunger

- Leptin high → body is fat and happily well fed → feeling satiated

When leptin was originally discovered, it seemed like a slam-dunk for fixing obesity. Just inject people with leptin and presto — they’ll quit eating. Ha ha ha! Wacky biodiversity! Joke’s on you, scientists! Turns out only a small percentage of obese people actually had a leptin deficiency.

Back to the drawing board.

Finding the sweet spot

By the way, lest you think I’m hatin’ on high GH, low GH is a problem too.

GH-deficient adults are insulin resistant— likely due to higher body fat, lower lean body mass, and poorer physical performance.

However, although they’re stronger, leaner, and denser, adults with with excess GH are consistently insulin resistant as well.

Biology — it’s all about the sweet spot.

There’s also a difference between acute and chronic for darn near everything in physiology.

Acute stress, in the right amount proportional to an organism’s recovery ability, that ends appropriately and satisfactorily in a timely fashion (with the physical discharge of any lingering trauma)… good!

Acute stress, too much for the organism’s recovery abilities, and/or which doesn’t have a satisfactory resolution… bad!

Chronic stress… super extra bad!

Acute GH pulses, in the right amount at the right time, probably good!

Chronic GH pulses, either too much or too often, probably bad!

Exclamation marks! Too many exclamation marks is also chronically stressful! Because I’m screaming, you see! And it’s good once! But then it’s just annoying! After a while it just grinds you down! See the point!? Of course you do!!!!!!!

When GH attacks

When do we have high levels of GH? Many factors can be involved.

Also be aware that with hormones, there’s always a range. The increased pulses of GH we’re talking about here may still be much less than someone with true excess GH. However, remember that these pulses could be higher than normal for a particular individual, and that’s what matters.

Barring anything like a pituitary or genetic disorder, increased GH secretion can occur in response to:

- high levels of ghrelin (one of the hormones, secreted in the GI tract, that makes us hungry)

- physical stress (e.g. intense exercise)

- nutrient deprivation — starting a few hours after a meal and particularly in the true fasted state (such as first thing in the morning after 8 hours or more of no food)

Now, remember that “nutrient deprivation” can be kinda vague, to the body. We’re wired to be attuned to potential starvation, especially as females. Reproduction is a low-on-the-list “nice to have”, especially given the incredible investment of physical resources required for pregnancy.

By the way, dig this — it blew my mind when I first discovered it — even persistent thoughts of starvation and restriction can trigger the starvation response (including menstrual disruption), even if you aren’t actually restricting. This is known as cognitive dietary restraint and it can screw you up just as bad as really doing it.

So — depending on your unique stress sensitivity — your body is hair-trigger-wired to sense any kind of stress or deprivation and shut that babymakin’ shit down ASAP if needed.

That “nutrient deprivation” stress can mean:

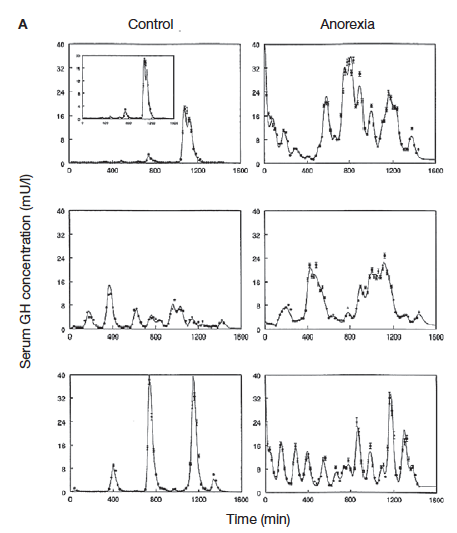

- generally low energy availability (i.e. fewer calories coming in than going out) (GH is typically high in anorexics)

- low macronutrient availability (i.e. significant deficits of fat, protein, and/or carbohydrates);

- low micronutrient availability (i.e. vitamins, minerals, quasi-hormones such as vitamin D, etc.); or even

- perceived low availability (as in cognitive dietary restraint).

GH secretion over time (using continuous blood flow measure) in control group (left hand column) and anorexics (right hand column). Notice how anorexics’ pulses are more frequent and often higher. From Lawson and Klibanski 2008. |

However, it appears that given GH’s relationships with insulin and IGF-1, and given women’s relatively higher levels of GH, carbohydrate restriction may be more salient than some other types of restriction. (Remember, this is a working hypothesis, but bear with me.)

GH resistance

In rats fed a low-carb, high-fat diet, bone growth and bone density was impaired. More concerning, the rats accumulated visceral fat and developed GH resistance.

(In case you’re curious, this occurred apparently regardless of levels of fat/protein, which suggests the determining factor was the availability of carbohydrate. However, adequate protein did appear to protect lean mass to some degree — as the researchers noted, “protein intake is of critical importance for the regulation of the GH/IGF-axis” — which reminds us that getting enough protein is key when running a caloric deficit.)

Hormone resistance can occur when hormone levels are chronically elevated.

Recall homeostasis — if something is persistently out of whack, the body will self-correct, or try to. So when a hormone is blasting through the system constantly, loudly announcing its presence, the body will often try to “turn down the volume” by making tissues increasingly “deaf” to that hormone.

Hormone resistance implies that you then get too-high circulating levels of that hormone, because tissues are less receptive to it. (Recall the explanation of insulin resistance, above.) The hormone still gets released, but tissues don’t give a shit. Now the hormone has nowhere to go. But it’s still there. And eventually, it has to go somewhere.

So GH resistance means potentially high GH without the tissues using it properly. It also means that the complex system of feedback that governs the actions of insulin, IGF-1 and probably related cell signalling molecules and other hormones are disrupted.

Now, rats aren’t people, of course. But it’s food (ha) for thought.

Remember, we probably want short, moderate, relatively regular blips of GH. Right amount, right time, right reason.

We also want all our hormones and cell signals playing nice with each other.

We want GH working properly with its buddies insulin and IGF-1. When insulin and IGF-1 are low (as, again, during periods of food deprivation), the “good” anabolic effects of GH (such as repair and regeneration) are often blunted, but the “bad” effects (such as insulin resistance) are often — eventually — elevated.

Somatostatin

Somatostatin is a hormone that’s produced both in the brain and digestive system, which gives you clues about its importance and mechanism of action. And it’s involved in regulating other hormones.

Somatostatin is basically a digestion killer. It suppresses the release of important gastrointestinal hormones:

- gastrin

- cholecystokinin (CCK)

- secretin

- motilin

- vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)

- gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)

- enteroglucagon

Somatostatin thus slows down gastric emptying and peristaltic muscle contractions as well as blood flow in the intestine. It inhibits the release of pancreatic hormones, insulin, and glucagon.

Somatostatin is released in response to high circulating levels of growth hormone (GH), and inhibits GH (in fact, it’s sometimes known as growth hormone-inhibiting hormone (GHIH)). Conversely, GH production is stimulated by (wait for it) growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH).

The perfect stress storm

So let’s imagine the possible scenario of consistently elevated GH and/or even perhaps GH resistance in the face of chronic stress.

1. Stress stimulates increased GH secretion.

2. GH is now persistently high. But now, because GH release is so frequent and high, maybe the tissues aren’t using it properly.

3. The body’s master controller notices that GH is high and releases somatostatin to inhibit GH.

4. Now somatostatin is high. And GH will eventually pop back up, because the stress persists.

5. Thus, possibly, we might have high somatostatin alternating with high GH. And neither hormone is doing good work. Instead, we’re probably seeing the worst faces of both. Frinstance:

Maybe high somatostatin is making digestion crappy. (Har dee har.)

Maybe high GH is lowering leptin (making you hungrier). Or creating insulin resistance. Or stashing TGs in the liver.

And — something I haven’t mentioned here, but it’s relevant — it’s a good bet that if your GH/IGF-1 axis is screwed up, other hormonal systems (such as your sex hormones, adrenal hormones, and/or thyroid hormones) are also screwed up.

In any case, if this proposed scenario fits your experience, you’re probably feeling lousy by now.

What does it all mean?

Hello? Are you still reading? OK good.

Let’s talk practicality.

What can you do right now to address any potential hormonal problems that might have occurred with nutrient deprivation?

If you think you have a hormonal problem related to the above set of circumstances…

Figure it out

Get tested. I suggest a full sex hormone panel plus thyroid and 24-hour salivary cortisol. GH/IGF-1/somatostatin tests are less common and typically only used where docs suspect GH deficiency or excess, particularly in children/teens. Start with your doctor/endocrinologist or a qualified naturopath and see what you can negotiate.

Make a complete list of everything you’re experiencing. Even if it doesn’t seem relevant (like sleep, or mood, or cravings). Start to become an archaologist of your own biology. Dig shit up. Pay attention. Check in. Learn your physical and psychological cues, such as:

- mood, anxiety/depression, mental health, cognition, irritability, etc.

- energy levels and fatigue

- quality and quantity of sleep; normal sleep-wake cycles

- heart rate

- body shape and normal fat gain patterns for you

- appetite, hunger, and satiety

- cravings and food behaviours

- physical performance and perceived effort

- immunity and injury/illness recovery

- digestion and GI health

- skin

- reproductive cycles and libido

- pain perception and awareness; shifting patterns of pain and/or inflammation

- sense of overall wellbeing and mojo

Almost nothing, if it happens more than rarely, is irrelevant.

Low-hanging fruit

If you’re fasting regularly, stop. Now. Just stop. Especially if you’re relatively leaner and exercising regularly.

Eat relatively regularly, every few hours when you’re genuinely hungry. You don’t have to be rigid about this, just be aware of your physical hunger signals. If you’re doing this right, you should be genuinely physically hungry about every 3-4 hours. Eat until you’re satisfied.

Eat breakfast. The folks who seem to genuinely do well with breakfast skipping tend to be young male ectomorphs who may have a different GH machinery than you. Alwyn Cosgrove — who documents his clients’ progress obsessively and now has hundreds of data points — says that whenever he gets his female clients to eat breakfast, they start losing fat. True story. Hormones have a daily circadian rhythm, which can vary between individuals. A morning meal for someone who’s previously been nutrient-depleted can potentially fire up the furnace again, because it can send a signal of “Phew, food’s coming in, we’re going to be OK!” to a body that is feeling pretty anxious about famine.

Add a small portion of slow-digesting, high-fiber carbs to every meal. It doesn’t have to be a lot. A cupped handful will do. If you’re far enough into hormonal fuckedupitude that you’re dealing with insulin resistance, your body needs time to recover and respond properly. Depending on your individual dietary tolerances and food preferences, opt for things like:

- sweet potatoes/yams

- other starchy tubers such as yuca

- potatoes

- bananas (green or ripe), plantains

- other fruit

- beans, legumes, peas, lentils

- whole, unprocessed grains (soak them first if possible)

My hunch is that starches work better than fruit here because of the way the brain perceives glucose vs. fructose. But don’t overthink this. Just put the frickin’ sweet potato in your appropriate sweet-potato-related orifice and get ‘er done.

Do your best to ensure good food quality here, and try to go as unprocessed and primal as possible (e.g. a baked potato beats a potato chip). I am definitely not giving you a license to go hog wild into the brownie tray. Keep it real and sane. Don’t bullshit yourself. But honestly, if you’ve been restricting like a mofo for a long time, the details are less important than just getting into the habit of steady carb intake. If you can tolerate bread with no ill effects, the occasional slice won’t kill ya.

Pay attention to how you feel. I know I already said that. But it bears repeating. By the time we start circling the hormonal toilet bowl, there’s a good chance we’ve ignored a lot of body cues.

Bigger-picture stuff

Review your eating habits and patterns. You may need to eat more in general, more carbs, and/or more often. There’s good news: Abnormalities in the GH–IGF-I axis are reversible with refeeding. Look at your intake and ask yourself: What might count as metabolic stress?

Remember that the cumulative load of stress is the real problem here. Being an anal-retentive dietary fussbudget will cost you. As will flipping out about every single fucking thing you eat. As will overtraining and under-resting. As will worrying about whether you’re going to die of face cancer from eating a bagel. Just eat the damn food and lighten up.

Kill stress. Kill it with fire. Root it out with extreme prejudice. Get real about your sleep, your psychological environment, your self-talk, your work habits, your training load and intensity, your (lack of) rest and recovery protocols, your expectations, your relationships, and everything else that could be draining your tank. Get over wanting to be a superhero and embrace your vulnerable humanity. It’s OK.

Stop reading shit on the internet (except me, of course, ha). Step away from the computer into the real world of YOUR body. Worry less about the details and more about the big picture. My whole hypothesis here could be totally useless for explaining YOUR situation. Doesn’t matter. Just follow the real-life evidence wherever it leads you. Got a theory? Great! How’s that working for YOU?

Stop saying “should” and start saying “is”. Maybe Dietary Protocol X should work according to Expert Y or Anecdotal Evidence Z… but if it doesn’t feel good for you, it doesn’t fucking work for YOU and YOUR body. That is what it is. If you argue with reality you will always lose.

Consider your unique “stress sensitivity” and metabolic blueprint. Again, forget about “should”. You are YOU. Special snowflake YOU. If you’re someone who’s typically more sensitive to other things like sensory input, light and noise levels, nuances of things, tastes and textures, drug doses, food intolerances, etc. there’s a good chance you’re more metabolically sensitive too. (Even if you’ve tried to kill your sensitivity, or numbed it out, or pretended to be a badass.)

Consider the source. If you’re a middle-aged woman, don’t listen to a damn thing that young males say, unless said young males have a wealth of hands-on experience and research knowledge in the field of middle-aged women’s health. And even then, be suspicious.

Match your body to the information. If you are female, start by understanding that hormonally and evolutionarily speaking, a female body — especially one of reproductive age — is not exactly the same as a male body. An older body is not exactly the same as a younger body. A body in 21st century Western society is not exactly the same as a Paleolithic body. A human body is definitely not a mouse body. (Yes, I know I mentioned a rat study above, but take it as a starting point rather than gospel.)

Think long-term. Something might be working great for you now. Will it work in a month? 6 months? A year? 5 years? Face up to the inconvenient question of sustainability.

Balance the seesaw. If you add stress in one place you must take it away elsewhere. If you’re trying to lose fat and/or training hard, you must actively chase recovery and restoration. You must also do de-stressing, parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) dominant activities such as low-intensity rambling (especially outdoors in nature while getting sunshine), yoga, relaxing swims, laughing, cuddling, meditation, etc.

Stay checked in. Calibrate constantly. Try something and observe how you feel. Remember that it may take time to notice the effects. Go slowly, step by step. Be generous with your time, self-love, and patience. If you’re deep into this thing, it’ll take you a while to get out.

YOUR body is your boss. Nobody else. Love it, and listen to it.

Final word: What’s the “best diet”?

OK smartass Krista, what do YOU think is the “best diet”?

Well, obviously, there isn’t a single “best diet”. But here are some guidelines.

Don’t be crazy. Like S/M, be safe, sane, and consensual. If food, eating, and reading/thinking/arguing about food/eating are taking over your life, that’s being crazy. Unless being crazy is your job, like me.

Lower the stress load. That might mean eating a little more carbohydrate than conventionally recommended by low-carb folks. It means eating enough to support YOUR needs, whatever those are. It means removing inflammatory foods (sugar, wheat, maybe dairy for some folks, etc.) as much as possible, calibrating based on YOUR symptoms and individual body blueprint. Both over-restriction and bingeing are stressful. Try to find a middle ground of…

Eat when you’re physically hungry, and stop when you’re satisfied. Learn the body cues that will tell you what both of these things are.

Eat real food. Not processed crap. Not “edible food-like substances”. Eat stuff that comes from the ground or the field or the water. Animals and plants will do nicely.

Help your body do its job of digestion and nutrient processing. Eat fermented foods and probiotics. Occasionally eat something from your garden without washing it (assuming no animals are using your soil as a litterbox). Keep your gut happy and healthy.

Eat slowly and mindfully, in a relaxed setting. Stress — of any kind — shuts down digestion and harms bacterial flora.

Chill the fuck out. Don’t overthink this. Be real. (See “Don’t be crazy.”)

References

“__ all the things” meme from Hyperbole and a Half. If you aren’t reading this blog, you totally should be. This artist is a friggin’ genius.

Insulin… An Undeserved Bad Reputation from Weightology. This blog gives you teh smart.

Bielohuby, Maximilian, et al. Lack of dietary carbohydrates induces hepatic growth hormone (GH) resistance in rats. Endocrinology 152 no.5 (May 2011): 1948-1960.

Lawson, Elizabeth A. and Anne Klibanski. Endocrine abnormalities in anorexia nervosa. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology and Metabolism 4 no.7 (July 2008): 407-414.

Møller, Niels and Jens Otto Lunde Jørgensen. Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects. Endocrine Reviews 30 no. 2 (April 2009) 152-177.

Simpson, K. J. Parker, J. Plumer, S. Bloom. CCK, PYY and PP: The control of energy balance. Appetite Control: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 209 (2012): 209-230

Vijayakumar, Archana, Ruslan Novosyadlyy, YingJie Wu, Shoshana Yakar, and Derek LeRoith. Biological effects of growth hormone on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2010 February; 20 no.1. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2009.09.002

Yuen,K.J.C., L.E. Chong, M.C. Riddle. Influence of glucocorticoids and growth hormone on insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetic Medicine 2013. DOI: 10.1111/dme.12184