STRONG! An interview with weightlifter Cheryl Haworth

Full disclosure: When I discovered I’d have the chance to interview Cheryl Haworth, my inner voice screamed like a 5-year-old girl on a sugar bender at a birthday party.

Squeee!!

You see, dear milennial babies, there was a dark and silly time when old men in suits decreed that girlpeople could not lift heavy things at the Olympics, because lo, their uteruses would explode and all males present would spontaneously be emasculated. Or something. Who knows.

Anyway, the point is, despite the lifting of heavy things being an athletic pastime pretty much since humans had the opposable thumbs and bipedalism to do it, women’s weightlifting was only added as an Olympic sport in 2000.

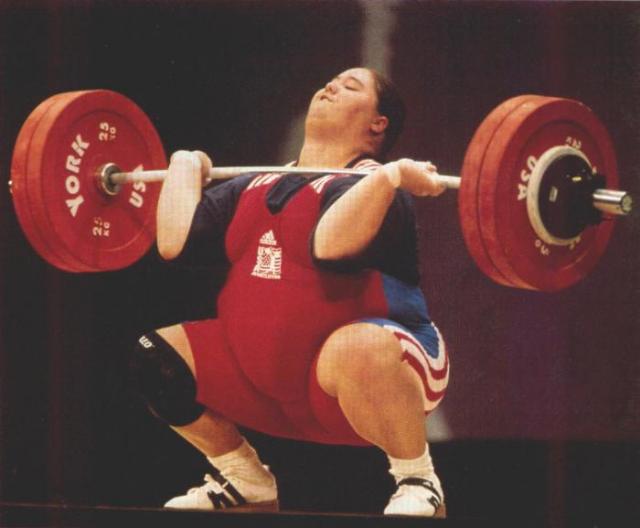

And one of the strongwomen blasting down the doors was Cheryl Haworth. Barely graduated from girlhood herself at 17, she stormed the platform and brought home a bronze medal for the U.S. in weightlifting.

In case you're wondering, those are 25 kilo (55 lb) plates. BOOYEAH!! |

It wasn’t just her performance that made the news, but also her youth, talent, and oh yeah — her size. It was one of the first times that a female superheavyweight strength athlete had been featured so prominently.

Media outlets were a-sputter, trying to deal with it.

Should they go for the teenage athlete prodigy angle? Should they go for the “It’s OK, because she’s still a Real Girl!” angle? Should they go for the “Holy crap, that’s an unbelievable amount of weight — how is that even possible?” angle?

Conventional pundits were utterly befuddled. I ripped Haworth-related articles out of magazines and filed them with both awe (for her) and a quiet, irritated sigh (for them).

It wasn’t until recently that filmmaker Julie Wyman was able to capture — respectfully and insightfully — the dignity, grace, and complexity of women’s weightlifting and female weightlifters, in her new film STRONG!

As the press release for STRONG! describes:

STRONG! chronicles an athlete’s struggle to defend her champion status as her lifetime weightlifting career inches towards its inevitable end. Cheryl Haworth defies categories. A 12th generation patriotic American, a visual artist, and, since age 14, America’s top Olympic weightlifter, she is an elite at the international level.

A formidable figure in American weightlifting. Haworth is ranked well above all men and women on Team USA. But at 5 foot 8 inches and weighing over 300 pounds, she doesn’t easily fit into standard chairs, clothing sizes, or pre-conceptions. As the 2008 Beijing Olympics approach, Haworth struggles with injuries, the end of her career, and the difficult task of re-defining herself and building a sense of confidence that she can bring with her as she leaves the sport that has given her a sense of pride.

STRONG! explores the contradiction of a body that is at once celebrated within the confines of her sport and shunned by mainstream culture. Through Haworth’s journey of strength, vulnerability, loneliness, and individuation, we learn not only about the sport of lifting weight, but also the state of being weighty: the material, psychological, and social consequences and possibilities of a having a body that doesn’t fit.

Wyman deftly captures Haworth’s experiences and goes beyond the two-dimensional media image to show Haworth’s complexity as a lifter, artist, daughter, and young athlete grappling with the demands of an elite career.

For more, check out:

I caught up with Cheryl Haworth in the midst of a whirlwind of publicity around the film’s release in mid-July 2012. (P.S. Squeeee!)

Q. How did you come to be involved in this film? What kinds of questions was the filmmaker interested in exploring with you?

A. Well, it was a pretty simple scenario. I was competing in 2000, the inaugural year for women’s weightlifting in Sydney. Our US team was getting a lot of media attention, especially with me being 17.

Julie Wyman, the filmmaker, was a sports fan and found this really interesting — thought I was an interesting character. She kept it in the back of her mind, until in 2004 she gave me a call and asked if I’d be interested in filming something short, maybe a documentary. I readily agreed. She flew to Savannah and we met and hit it off. We became fast friends. Initially she was just a person who was really easy to talk to. Over time, the documentary grew legs and became something else entirely.

The way the film evolved was very organic. It’s so watchable. Julie had no preconceived notions about weightlifting, or what she thought the film should be, so she didn’t force it into anywhere it wasn’t going to fit, or where it didn’t belong.

She’s inquisitive, so she has a knack for asking questions, and had a real curiosity about weightlifting. And she asked the kinds of questions that other people are thinking about. She’s exploring everything, every nook and cranny.

So that translated nicely into a film that was a bit educational. People can watch this film and learn about weightlifting itself, how it’s different from other sports, the breakdown of the movements and how they’re choreographed.

The response has been amazing. Whether you’re an Olympic weightlifter or not, a lady or not, younger, older, it doesn’t matter. Everybody has been able to pull something from the film, whether it’s inspiring someone to get in the gym, or just having people realize that there’s an incredible level of grace and determination, and perseverance thru disappointment, in this sport.

For example, there was a screening at a men’s prison. There were many layers of security, which was intimidating, but these guys were my biggest fans. Some of the men were in tears, because they took the film as something they could use in their own lives, as inspiration to do what they need to do when they get out of jail.

We realized then that this movie was about so much more than picking up heavy things.

|

|

Q. In the film, there’s a theme of alone-ness and isolation. Weightlifting is a solitary sport — you’re all by yourself on the platform — but there’s also a sense of larger social isolation as a female heavyweight strength athlete. Can you talk about the role that being alone played in your experience?

|

“I’ve been to the Olympics twice and I graduated from college. What do you want from me?” –Cheryl, to her mother, in Strong |

A. Well, on the one hand, you are part of a team mentality, especially competing in an underdog sport that doesn’t get a lot of attention, where you have to shake things up and say “Look at me!”

And it never got too stressful for me to be the anchor. Everyone on the team was always crunching the numbers, everyone was always done before me, and then they’d just expect, “Oh, Cheryl’s going to come through and get the points for us.”

That was always my role. To finish things up strong. And fortunately, being a competitor, I always enjoyed that.

On the other hand, being a weightlifter and having so many people be completely oblivious or unaware of your sport and the fact that you’re dedicating your life to it can be frustrating. It’s interesting now, watching the Olympics, and being a spectator, and taking a look at what my fellow American is most interested in watching. I’ve seen so much swimming, and gymnastics, which are great sports, but there’s a lot of other things happening, and a lot of these sports are individual.

So there’s that struggle. And part of me feels like it’s an easier struggle if you’re in a sport that people want to watch. There’s being an individual competitor in a celebrated sport, and then there’s being an individual competitor in a sport that nobody watches.

Q. There’s a larger cultural fascination with athletic women’s bodies in our society. Women’s bodies are often seen as public property or a public spectacle. What’s your experience with the way that media have depicted your physicality as a heavyweight athlete?

A. It’s frustrating, because it’s like instead of “Oh, you’re the strongest woman in the history of the US”, it’s like “You’re big but you don’t sit on the couch and do nothing. How does that work?” They just don’t understand that bigger people can be elite athletes.

Although my sport is very specific and I use my size as an advantage, it shouldn’t be such an odd concept. That’s a big part of what Julie explores, and what she wants people to realize about weightlifting, that there are a lot of different competitors in different bodies.

When folks find out that I’m an artist as well — I paint, I draw, but I’m also an athlete — that’s odd. But instead of blaming people who ask those questions, I’m curious, as julie is too. Why do we ask those questions? Why does everyone think that’s odd, to be both an athlete and an artist?

Q. The film explores the way that weightlifting isn’t just about moving a heavy thing — it’s about understanding how your body works in relation to timing and momentum and inertia, and basically the physics of movement. Tell me about that.

A. The first time i saw Olympic weightlifting, I was captivated not only by the idea of human beings handling so much weight, but also by the speed and the agility and the grace with which these athletes were performing these maneuvers. Even at 13, when I didn’t know what I was getting myself into, I loved the way it looked. That’s how i got bitten by the bug.

I’m a strong person, obviously, physically. Yet compared to a lot of female weightlifters, even in this country, there are plenty of ladies who are pound for pound, or overall, even, stronger than I am. The only way I was successful was to really, really, really cultivate a technique that works for my body, and one that I was very disciplined in maintaining.

I’m not strong enough to make any mistakes. If my snatch is moving backward, I’m not that person that can force it into the postiion it has to be in.

People would comment on my weightlifting and say it looks so effortless. They’d say “Put more weight on the bar.” But if I did put more weight on, my technique would go, and I wouldn’t be able to lift it. If I didn’t get it perfect, then I couldn’t do it at all. It just wouldn’t happen.

It’s a movement that captivated me. It’s so interesting. But I had to adhere to it very strictly.

Q. Recently Sally Ride, the first American female astronaut, died. Newscasters talked about the kinds of questions she got asked in the 1980s, one of which was “Are you planning to wear a bra under your astronaut suit?” As a pioneer yourself, you must have been on the receiving end of a lot of dumb questions. Can you tell me some of those?

A. There were some humdingers. I get really annoyed, maybe it’s because i’ve heard it so much, when people worry about me dropping weights on my toes. My toes, gosh, no it’s not a problem. It’s fine.

Then there’s, “How much do you bench press?” God bless ‘em, American men especially, it’s the thing you do in the gym, y’know? As a dude, you go over and you bench press, it’s what you’re supposed to do. Everyone appears so crestfallen when I say I don’t bench press.

Q. Strength coach Charles Staley once said to me that if you’re NOT afraid of getting under a heavy weight, you are probably mentally ill. In the film you say it’s “easier to talk yourself out of it than into it”. What kind of courage and mindset is required in order to dive under a heavy weight?

A. When it comes to mindset, there were a couple different phases in my career.

At first, I had the carefree, happy go lucky, i’m never going to be injured in this sport, attitude. Like in 2000, winning my bronze medal, lah dee dah, going through the motions, I never felt afraid at all, ever.

Then there was the elbow injury [in which Cheryl tore two ligaments], and I was like “Oh yikes, that was pretty painful, how does one deal with that?”

Everyone has different approaches. For me, there’s a commitment to lifting the bar. Even when you know your joints could separate. I simply ask myself: “Do I want to be a weightlifter?”

Do I hesitate? “No, Cheryl, you can’t do that. You can’t lift the bar if you hesitate. Commit to every motion.”

Then there were times that were more stressful than others. Where I’d think too far ahead. In that case I’d trick myself. I’d think “OK, I’m at a competition, and all I have to do is snatch. Just snatch. That’s all. Then I’m done.”

Whatever the result of the snatch, I’d turn around and pretend I just got there. Then I’d say, “OK, all I have to do is clean and jerk. Just clean and jerk.” I’d compartmentalize the lifts. Compartmentalize the stress.

To be honest, I was always a competitor. I felt like I was wasting my time until I was on that platform in front of a group of folks watching me, until the moment was critical, and it felt like the most important lift of my career. I always loved those moments.

I always knew when I wasn’t going to make a lift. Sometimes, when you have doubts, you can talk yourself into something. You can shake it off and refocus. But if I doubted myself, that’s usually when I wouldn’t make the lift.

|

|

Q. In the film you draw a poignant comparison between your own body experiences and the requirements of the sport, and you say: “You begin to hate what you do because it’s keeping you trapped somewhere.” Can you talk about that?

A. There are moments where you find yourself in the middle of something, and you wonder how you got there, when things are falling apart, when you’re not feeling as good as you used to, and you’re wondering, “What am I doing?”

I had a few of those moments, and a lot of the time it had to do with size, and dealing with society, and shopping for clothes, and that kind of nonsense, and then going into the gym and being awesome. It was a really interesting catch-22 i found myself in. It’s a really bizarre feeling.

Q. What might people be surprised to know about weightlifters?

A. The casual viewer thinks that all weightlifters are like me. Really big people, really big muscles. But in reality we have 7 weight classes for women and 8 for men. Weightlifters come in all shapes and sizes. It’s not an army of superheavyweights.

Most people think weightlifters are just enormous. The tiniest and the largest weightlifters make up a very small percentage of the competitors. Most of them fall into those middleweight classes.

|

|

Q. What are you most proud of? I don’t mean external rewards like medals, but rather moments of growth, or insight, or personal achievement that were really meaningful to you in your career?

A. One that i don’t really talk about too much happened in Beijing. I was so out of shape from the injury, and so forlorn, just really sad about having to compete when I knew the only thing that was going to happen was that I was going to embarrass myself.

You can’t pull a big lift out of your ass if you’re not in shape. You just can’t. Well, maybe you could rescue a baby under a car, or something.

But in competition, this lift wasn’t going to happen, and I knew it. For a little while, I was thinking of any way to get out of the competition. What can I do to not have to get on that stage? Maybe if i get hurt, maybe if something happens, just anything, to get me out of that. It’s a very human response; nobody wants to embarrass themselves in such a way.

But then I began to think about my parents flying across the world, and my best friend sitting at home who was the alternate, and there’s no way she could have gotten there in time. It wasn’t a sacrifice, obviously my duty is to go and perform, no matter what.

So, I was proud of myself for facing the music, even when I wanted to be somewhere else so badly. Never more so than in that moment there.

I took 6th and was complaining to a teammate of mine about not doing well. He’d bombed out earlier, didn’t even place. Here I am, griping about being 6th, and he said “Well, at least you totaled.” And I was like, “Oh my God, I’m so sorry.”

As an athlete, you’re trained to think about yourself all the time. It’s so selfish, but you’re trained to do it. What you’re eating or not eating. Whether you’re recovering. Your performance. Whatever. That carries through. And that was the moment where I was like “Cheryl, shut up. Just shut up and turn straw into gold.” I ended up having a great time with my family.

But I think what’s hard for people to understand is that at this level, it’s not about just showing up, or getting to be there. It’s about going and knowing I’m going to be one of the strongest women in the world, because I am. I wanted to do well. And honestly, I still feel that silver medal should have been mine. It’s not anyone’s fault, because I was injured and couldn’t perform. But still.

That’s the athlete mentality. It’s a double edged sword: It keeps you working hard, but it also makes you a bit crazy!

Q. What are you up to these days?

A. I recruit for the Savannah College of Art and Design. It’s where I got my BFA. I’ve been travelling a lot. If i get a chance to work out, it’s a hotel gym. I love working out. I love training. I don’t get to do it as often as I want. I don’t have any muscles any more!

Q. What advice would you give to new women weightlifters?

A. To the folks that are completely new, like “I don’t know what Olympic weightlifting is, or what it’s all about, it’s really an amazing sport that’s so good for almost all that ails you. It’s a sport that all Olympic athletes do, whether they’re weightlifters or not. It’s so good for power. For women especially, the bone density factor is incredible. I don’t think women realize the health benefits associated with weight-bearing exercise. So women interested in learning weightlifting should at least explore the options they have locally, and learn that there are lots of possibilities.

For new competitors, it’s about confidence. That’s a simple answer to give, but when I think about my experience, there were moments when I had to talk myself into things. And that doesn’t mean you’re no good. Just because you have to convince yourself to do things doesn’t mean you’re beaten. It’s just part of being a competitor.

Don’t get too upset about training. I don’t remember any workout that I ever had where I sat down and I cried about it. Not once. And I’ve had my share of miserable workouts. So maintain a balance. Don’t get too caught up in it. Leave whatever happens in the gym.

That was one of the hardest things at the Olympic training centre. We’d sit around after we worked out, over lunch, and everyone would be talking about the next workout. And I was like, “I don’t care. I don’t want to know. I want to go in there with a clean slate.” I wanted to be very present.

Be present. Because you can’t think too far ahead. You’ll mess yourself up bigtime! Be present — that’s just great advice for life.

|

|